I just spent ten days backcountry skiing in Colorado and then, back home in Vermont, spent a few days thoroughly enjoying my 13 month old granddaughter Elizabeth while her mother was away in Oregon. Those activities have helped me enjoy a strange winter here in Vermont, one that has teased us with snow several times, only to laugh at our hopes while thrashing us with ice or rain. The break has also rejuvenated my blogging ardor, so after a three week hiatus, here we go again.

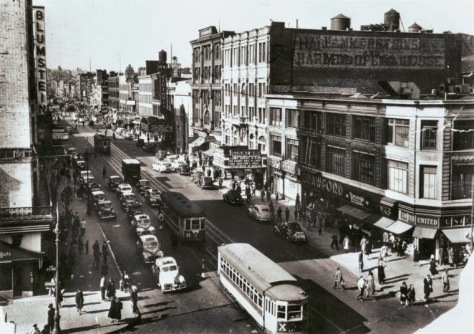

My parents began their life together in wartime New York City. I’ve done a little research to help me picture their life in 1943. What were the streets like, the people, the traffic? I’ve found some images that help, including this one from that year taken on W 125th street, a couple of miles south of their apartment in Washington Heights.  There is a young woman in a fur coat nearing the lower left corner wearing a fur coat just like the one I can remember her wearing. It helps me imagine her there that November of 1943, 23 years old, energetic and full of expectations of her life to come, not yet full of the fear that would plague her a year later when Jim shipped out for war torn Europe.

There is a young woman in a fur coat nearing the lower left corner wearing a fur coat just like the one I can remember her wearing. It helps me imagine her there that November of 1943, 23 years old, energetic and full of expectations of her life to come, not yet full of the fear that would plague her a year later when Jim shipped out for war torn Europe.

In those days New York was a white city, in fact over 90 percent white. While there was a refugee crisis in Europe (sound familiar?) the United States adhered to strict quotas, harboring the same fears that are echoed today. The Lower East Side in Manhattan was home to a burgeoning immigrant population, but uptown where my parents lived was the milieu of the white, protestant families that dominated the city. Nearby Harlem was the center of the black population, and the scene of growing unrest. On August 1 and 2, 1943, a race riot erupted there in response to the shooting of a black man by a white police officer. Things don’t change much, do they?

For my parents, the city was a crowded, bustling place full of promise. My father knew it well from his years in New Jersey, and his parents maintained an apartment on lower 5th Avenue, where Jim and Liz were frequent dinner guests. Rents were affordable for working families, and I’m sure the two of them must have been comfortable on their combined modest incomes. Both of their lives centered around the Columbia Presbyterian hospital complex. My mother had her first job as a medical social worker, while my father worked long and crazy hours at Babies Hospital. They grabbed moments together, occasionally meeting for lunch in the hospital cafeteria or one of the ubiquitous delis in the neighborhood. Their apartment was just a few minutes’ walk, so despite his schedule, my father was able to be home for dinner much of the time. Both of them came from households with a maid who did much of the cooking, so I suspect that my mother was learning on the fly, settling into a routine of cooking for her husband’s tastes, to which she catered for the rest of her life.

They knew the life they were building was temporary, and in March of 1944, ten months after their marriage, the inevitable happened when my father was called to active duty. He was commissioned as a First Lieutenant, and sent to Army Field Service School at Camp Carlisle in Pennsylvania, where a six week orientation for medical doctors took place. My mother kept her job in New York, but spent two weekends in Carlisle. Jim said the most important lesson he learned there was that there are regulations for everything in the Army, and no matter what a medical officer might need, somewhere there was a regulation permitting it. Jim was learning how to deal with bureaucracy, a skill that served him well throughout his career.

The next step in training was a six week stint at an army hospital to learn “army medicine”. Jim was assigned to LaGarde General Hospital in New Orleans. Officers were allowed to take their wives, so Liz took a leave of absence and the couple began six months of nomadic life, knowing their time together would end when Jim shipped out to an uncertain future for an uncertain amount of time. Every hour began to be important.

My parents were one of literally millions of couples who decided to get married despite the war looming on the horizon. Jim had actually joined the US Army Medical Corps reserve in the spring of 1941. From his experiences in Germany in 1935 and 1938, he was sure we would be drawn into the war, and knew that doctors would be in high demand. Indeed, medical school was accelerated beginning in 1942. By shortening the summer holiday a class of doctors was graduated every nine months. This continued until the war’s end in 1945. I never discussed with my parents their thoughts around marriage and impending military service, except that my father told me that they decided not to have children until after the war. I know from their letters around the time of their engagement that they were deeply in love. Here’s an excerpt from Liz’s letter to Jim on Christmas day, 1942, after they had just spent five days together with Jim’s family.

My parents were one of literally millions of couples who decided to get married despite the war looming on the horizon. Jim had actually joined the US Army Medical Corps reserve in the spring of 1941. From his experiences in Germany in 1935 and 1938, he was sure we would be drawn into the war, and knew that doctors would be in high demand. Indeed, medical school was accelerated beginning in 1942. By shortening the summer holiday a class of doctors was graduated every nine months. This continued until the war’s end in 1945. I never discussed with my parents their thoughts around marriage and impending military service, except that my father told me that they decided not to have children until after the war. I know from their letters around the time of their engagement that they were deeply in love. Here’s an excerpt from Liz’s letter to Jim on Christmas day, 1942, after they had just spent five days together with Jim’s family.

Jim was a precocious student and went to private school, graduating from Lawrenceville at the age of 16. His letters from that time are full of his eager participation in everything the school had to offer, as well as careful accounting of his young finances. His parents wanted him to take a year off before going on to college, and Jim wanted to become fluent in either French or German by living in Europe for a time. His parents thought France was too decadent for a seventeen year old boy, so they agreed that he would live in Germany for three or four months, and found a family that would board him. In January, 1935 Jim arrived at Frau Sauer’s house at Oberlindau 94 in Frankfurt. His exposure to Nazi Germany had begun, and I looked forward eagerly to his letters.

Jim was a precocious student and went to private school, graduating from Lawrenceville at the age of 16. His letters from that time are full of his eager participation in everything the school had to offer, as well as careful accounting of his young finances. His parents wanted him to take a year off before going on to college, and Jim wanted to become fluent in either French or German by living in Europe for a time. His parents thought France was too decadent for a seventeen year old boy, so they agreed that he would live in Germany for three or four months, and found a family that would board him. In January, 1935 Jim arrived at Frau Sauer’s house at Oberlindau 94 in Frankfurt. His exposure to Nazi Germany had begun, and I looked forward eagerly to his letters.